This past Saturday marked an amazing end in the world of obscure border disputes and cartographic oddities. After nearly 70 years India and Bangladesh have resolved a border dispute in the Cooch Behar region by agreeing to swap enclaved territory. An enclave for the not so geopolitically inclined, is any portion of a state that is entirely surrounded by the territory of another state. The resolution of the border dispute surrounding Cooch Behar is particularly noteworthy because it removes the only third-order enclave in the world – an enclave surrounded by an enclave surrounded by an enclave surrounded by another state - from the map. While this particular situation may be unique, enclaves come in many varieties and are not uncommon. Many similar multi-order enclave conditions exist along the Dutch/Belgian border. From coastal enclaves like Alaska and Kaliningrad, to enclaved territories such as Lesotho and Vatican City, and even Dallas’ own Cockrell Hill and Park Cities, enclaves can be found at all geopolitical scales. No matter the scale, all have an impact on the people living within them who can face restricted travel or are limited in access to goods, schools or electricity.

Enclaves

At an entirely different scale, a similar condition is shaping the city of Dallas. But it’s not likely to make headlines anytime soon even among cartography geeks and most won’t notice any restrictions on their day-to-day lives. I’m referring to zoning regulations and their impact on the urban fabric and built form is easily identifiable. These overlapping, conflicting, outdated, and often arbitrary rules are more than simply nuisances for architects, planners, and developers. Just as the mess of enclaves in Cooch Behar have a real impact on the people who must navigate the landscape of shrapnel wound jurisdictions, overly prescriptive, piecemeal zoning regulations lead to urban form which is the visual and spatial equivalent of clanging.

Zoning regulations and planning restrictions are nothing new and the differing strategies employed throughout the world have helped to generate a myriad of unique urban conditions. The first zoning law in the United States, the 1916 Zoning Resolution of New York City, limited building mass at certain heights in order to allow light and air to reach the street. Set up as a simple formula, it was popularized shortly after its adoption through the dramatic illustrations by delineator Hugh Ferriss, and lead to a distinct architectural style employed far beyond New York. It is important to note, 1916 resolution was a form-based regulation placing no restrictions on the activities occurring inside the building. The “culture of congestion” still reigned free, albeit within the confines of limited setbacks.

Hugh Ferris

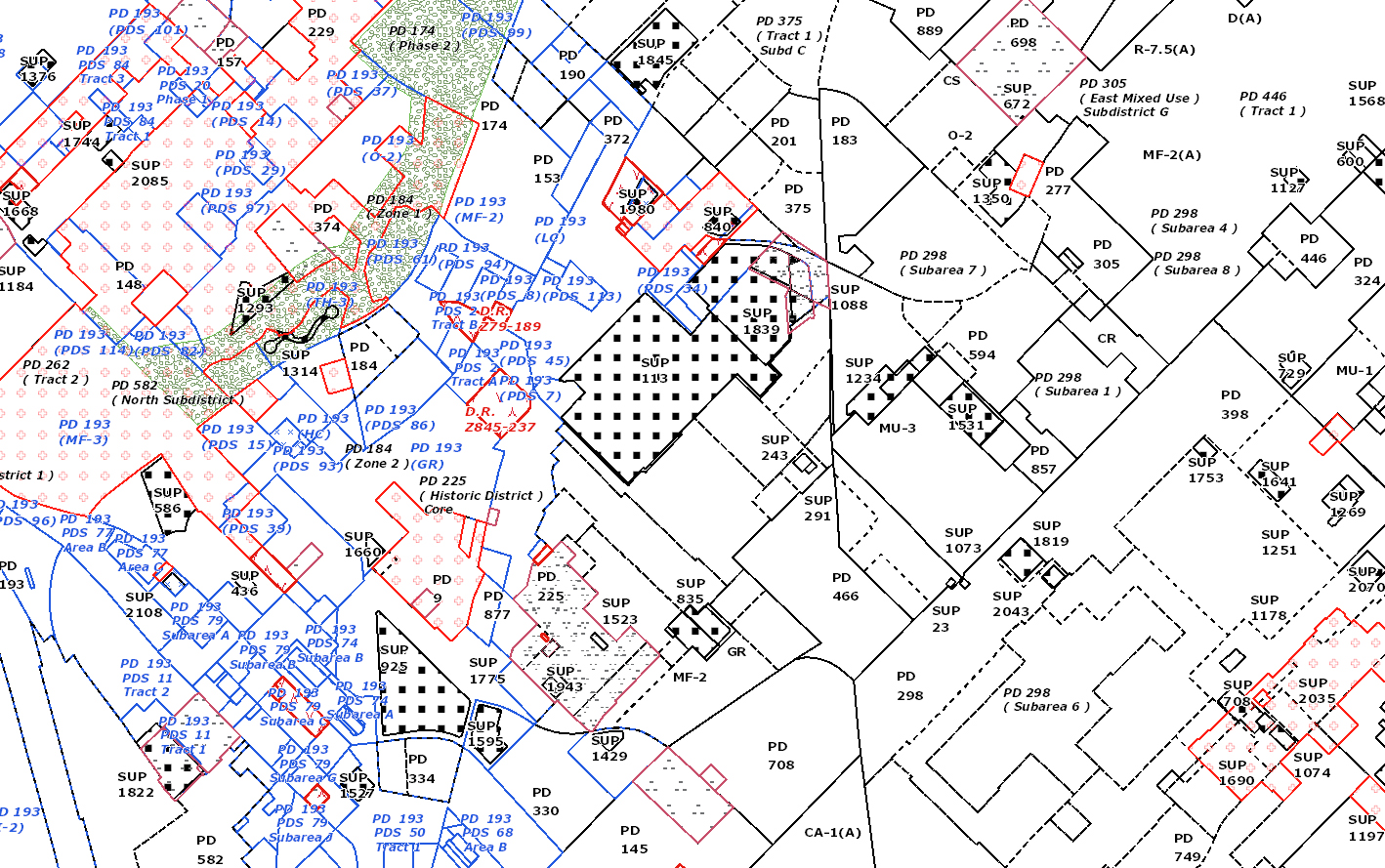

Dallas, like most cities with large growth after WWII, employs primarily use-based planning strategies which creates distinct zones for different building uses; industrial, commercial and residential most generally. Dallas has defined 45 different Zoning Districts each with their own set of rules. Within those, Planned Development Districts (PD)can be created to allow for special uses or building forms. There are currently over 900 PDs throughout the city, which are still apparently not enough given the additional Specific Use Permits (SUPs), Historical Overlays and additions of form-based strategies. A glance at the City of Dallas GIS zoning overlays clearly illustrates the pathwork of interlocking and overlapping areas. Despite all these regulations with the supposed goal of creating a functional, cohesive city, Dallas is left in a situation not unlike Houston. A city with no zoning regulations, comprised of disconnected patchworks held together by the loosest of connections.

PD Madness

Central to the current method of zoning regulation is an inherent view of urban planning which has been central to the planning of cities for centuries. That of a strictly rational approach to planning born out of the Industrial Revolution which views the city and the spaces and people which comprise it as elements to be ordered, compartmentalized and reduced to standards. It worked for industrial production, why not transportation, education, and urban planning? The issue, to use the cliché, is that a city is much more than its constituent parts. When attempting to standardize something as complex as an urban network of millions of people, businesses, institutions, spaces, goods, etc., an understanding of the dynamic between them is lost and the outcome is generic and lifeless.

The answer is not the wholesale abandonment of the regulations that are in place and rely solely on market forces to dictate urban form (the Houston model). Rather than rethinking the zoning strategy we must shift the way we view cities and infrastructure. Modern technology, big data, social networks, and the sharing economy are changing the way we look at information, communication, travel, entertainment, industry, and education. Urban planning can gain much from these developments.

Is there not a urban planning strategy that can allow for unbridled economic profit making, so fundamental to the Texan ethos, while not also looking at what we call a city as nothing more than a web of infrastructure to be cataloged, streamlined, economized, which disregards the true complexity and wild nature of material interaction?

Let’s release ourselves from the systemic enclaving and focus on a new model. And let’s try to do it in less than 70 years.

Ryan is a designer who can’t legally call himself an Architect. A transplant from Cincinnati, he has spent time living, working and cycling on all continents except that one with nothing but penguins. He lives with his fiancé in Deep Ellum. Twitter @SMLXS Instagra @S.M.L.XS.